VISIONS OF THE NORTH

The Terrors of the Frozen Zone, Past and Present

Tuesday, January 27, 2026

Lost as Where We Are

Friday, September 19, 2025

The End of an Era

The news came buried in the ninth paragraph of an (otherwise welcome) update on the 2024 dive season, which included fantastic new photographs, including one of the ex-railway engine in the hold of HMS Erebus, a sight which so many of us had sought for so long. We can now imagine Franklin's men donning their leather raincoats, sleeping in their numbered hammocks, and pouring milk out of their blue 'Tam-o-Shanter' pitcher, with artifacts suddenly brought to the surface and the light of day. The Fraser Patent Stove, which brought warm air to sundry parts of the ship, is now revealed, as is one of the coal bunkers. And, while it's true that there will, for now, be no new dives, there is (I'm sure) much more imagery to come; from what I can see, many of the shipboard images appear to be stills from videos, whose other footage may not yet have been completely analyzed; the same may be true of other things we've only glimpsed so far.

And there's other good news to set against our disappointment: the Nattilik Heritage Centre has now opened a long-anticipated new wing, one designed for the safe storage and display of actual artifacts from the ships, there in Gjoa Haven where many of the descendants of Inuit whose eyewitness accounts led to the finding of Erebus live. And, back in Portsmouth, there's confirmation that the relics from the earliest dive seasons, including the ship's bell of Erebus, have safely arrived (and will hopefully at some point be on permanent display) at the National Museum of the Royal Navy.

Back when HMS Terror was found in 2016, I was asked by the anchor of the CTV evening news how I felt now that the mystery had been "solved." Of course, I had to point out that it wasn't solved at all -- using the metaphor of an onion, each of the layers of which must be peeled back patiently, I replied that what we had, now, was simply a much larger onion. I suspect that that, between the materials already brought up by the UAT, and the continuing work of archaeologists on land, we've still got a good deal more peeling to do.

Saturday, July 12, 2025

New manuscript of John Rae's Voyages and Travels

The photocopy, in that matter, was a disappointment; it added nothing about any particular recipient for the original text. However, from other materials in the same folder, Mike and I learned that the pencil version -- a copy rather than a source for the printed text -- had in fact been made for a gentleman named "Mr. Silver"; in an accompanying cover letter, Rae apologized that he had no copies of the pamphlet to spare, but had quite generously copied out the full text by hand. But who was this Mr. Silver?

Stephen William Silver, a London businessman, was known for much of his career for the concern he owned and managed, the India Gutta-Percha and Telegraph Works Company. In a manner similar to many other captains of industry, he was also a member and supporter of a number of learned societies, among them the Royal Geographical Society, of which he was elected a Fellow in 1856. Along with Dr. Rae, he served on its board, and they were likely acquainted from that moment. Silver had a lifelong interest in exploration, though his main focus seems to have been Africa -- but, apparently, he was interested in the Arctic as well. But how did this letter end up in Australia?

The answer lies in the person of a gentleman named Edward Petherick, who served as Silver's "bibliographical advisor." When Silver died in 1905, Petherick was concerned that the collection might be broken up, and seems to have written a friend in Adelaide about the possibility of the Public Library of New South Wales acquiring it; when that was politely declined, Petherick worked through friends and associates connected with the RGS, via which it was eventually acquired with the intent of passing it along to the RGSA. As the "York Gate Library" it was warmly received, eventually being housed in the State Library of South Australia, where it was opened with some fanfare in 1908.

And so, while this discovery doesn't tell us much new about Rae's open letter, it does say something about the man himself: that he would take the trouble, for a friend and colleague, to copy out his whole article again by hand, just for his solitary benefit.

[The author would like to acknowledge his reliance on Valmai Hankel's excellent article, "Not Silver but Gold: S.W. Silver and the York Gate Library" (2005), for details as to Silver's collection and its transfer to Australia.]

Thursday, September 26, 2024

On the finding of James Fitzjames

Sir John is very well and full of life and energy - and we are all as happy as possible looking forward to the commencement of our real work - No one I am sure will rejoice more than yourself at our success which we all anticipate eventually if not sooner.

My dearest Elizabeth, the end will come with you in my thoughts and your picture clutched in my hand. Remember me fondly. For the last time, I wish you Good Night.

Thursday, August 1, 2024

New details on the career of Stephen Samuel Stanley

Sunday, February 4, 2024

The Mystery of Catherine Tozer

More recently, a lengthy research article on the Tozer family has come to light, compiled by a user known as @dustygnome; a link to this article may be found via Tumblr. There's a tremendous amount of valuable information in this article, which covers several generations of the Tozer family. I've also located a couple of additional resources in more specialized archives, including this trans history page which links to a newspaper article that contains an actual interview with Charley Wilson conducted shortly before his death. From this site, it's also fascinating to learn that Wilson was employed painting ships for the Peninsular & Oriental shipping company, including the Rome, the Victoria, the Oceania, and the Arcadia. P&O, as it was known, continued in business until 2006, when it was sold to DP World; a reconstituted part of the company operates P&O Ferries, infamous for sacking its entire staff in 2022. Charley Wilson is said to have died in 1911; I have so far been unable to locate a burial site.

Wednesday, January 24, 2024

Parks Canada 2023 finds

|

| Marc-André Bernier examines the seaman's chest |

Monday, December 25, 2023

Repost: Christmas in the Frozen Regions

"THINK of Christmas in the tremendous wastes of ice and snow, that lie in the remotest regions of the earth ! Christmas, in the interminable white desert of the Polar sea ! Yet it has been kept in those awful solitudes, cheerfully, by Englishmen. Where crashing mountains of ice, heaped up together, have made a chaos round their ships, which in a moment might have ground them to dust; where hair has frozen on the face; where blankets have stiffened upon the bodies of men lying asleep, closely housed by huge fires, and plasters have turned to ice upon the wounds of others accidentally hurt; where the ships have been undistinguishable from the environing ice, and have resembled themselves far less than the surrounding masses have resembled monstrous piles of architecture which could not possibly be there, or anywhere; where the winter animals and birds are white, as if they too were born of the desolate snow and frost; there Englishmen have read the prayers of Christmas Day, and have drunk to friends at home, and sung home songs."

"In 1819, Captain Parry and his brave companions did so ; and the officers having dined off a piece of fresh beef, nine months old, preserved by the intense climate, joined the men in acting plays, with the thermometer below zero, on the stage. In 1825, Captain Franklin's party kept Christmas Day in their hut with snap-dragon and a dance, among a merry party of Englishmen, Highlanders, Canadians, Esquimaux, Chipewyans, Dog- Ribs, Hare Indians, and Cree women and children.

In 1850, some commemoration of Christmas may perhaps take place in the Frozen Regions. Heaven grant it! It is not beyond hope ! and be held by the later crews of those same ships ; for they are the very same that have so long been missing, and that are painfully connected in the public mind with FRANKLIN’S name."

Thursday, September 28, 2023

Franklin's knowledge of the Daguerreotype Process

Franklin himself, though, was already quite familiar with the Daguerreotype process, and indeed with Richard Beard's studio. Francis Russell Nixon, the newly-consecrated Bishop of Van Diemen's Land, had in fact brought with him several of Beard's Daguerreotypes when he arrived in Hobart Town in 1843, and it's very likely Franklin saw them. Nixon also showed them to Alfred Bock, who was so delighted by them that he embarked on what was to be a lengthy career as one of Australia's pioneering photographers. Bock tried to establish a commercial studio, but was discouraged when George Barron Goodman -- who had purchased a sub-patent from Beard -- complained about Beck's advertisements. This pushed the opening of his establishment to 1847, though he seems to have been privately active as a photographer throughout the period of the delay.

.jpg) |

| Dr. William Bland, by Goodman |

The takeway from all this is that Franklin, either through Bishop Nixon (who became a close friend of the Franklins), Bock (who was the son of the ex-convict painter Thomas Bock, known for his portrait of the Franklins' adopted daughter Mathinna), or Goodman, was surely acquainted with the Daguerreotype process. Further confirmation comes via an item published in the very first issue of the Tasmanian Journal -- the organ of the Royal Society of Tasmania, founded by the Franklins -- in which an excerpt from a letter from Dr. Richardson to Franklin was published, touching specifically on Daguerreotypes, their use in photographing natural history specimens (!), and a method for turning them directly into printing plates in order to reproduce them. While this method -- which was destructive of the original Daguerreotype -- never caught on, the fact that Franklin and Richardson were discussing it with such easily familiarity as early as 1840 seems quite clear evidence that both men had already taken a keen interest in the process, even before local operators arrived in Hobart.

|

| courtesy Sotheby's |

Thursday, September 21, 2023

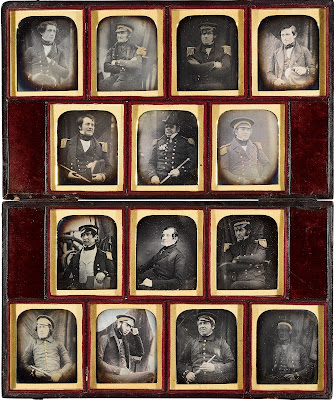

Richard Beard, the Daguerreotype and the Images of the Franklin Expedition

Guest post by Frank Michael Schuster

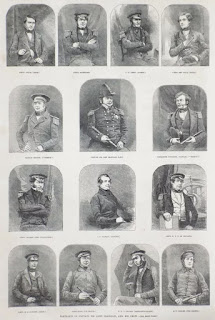

The month of May 1845, when Sir John Franklin's expedition set sail started out as a cold and unfriendly one throughout Europe. An outbreak of the flu was raging in London, which had also caught the expedition's leader. But by mid-May the weather improved and the 15th and 16th of May were sunny and noticeably warmer than the days before and after. Perhaps that was why a camera operator, or as they called it in those days, a Daguerreotypist from one of Richard Beard's studios, was just then coming on board HMS Erebus. He had been commissioned by Lady Jane Franklin to take photographs of Sir John and the other officers of the flagship, as well as Franklin's second-in-command Francis Crozier. With the help of a heavy curtain and a simple wooden chair, a makeshift studio was created on deck, where the men, supervised by the officers, still stowed provisions and other supplies. This might be why the officers in the pictures are wearing only their "undress uniform" instead of one of the more formal ones usually more appropriate to the occasion. Some, like Lieutenant James Walter Fairholme, are not even wearing their coats given the surprisingly mild weather. For, when it was his turn to be photographed, he simply borrowed “Fitzjames' coat [...], to save myself the trouble of getting my own,” as he later wrote to his father (Potter et. al., May We Be Spared 146). Unfortunately, we know nothing about the wind on those days, but the camera operator obviously wanted to take advantage of the sunny day.

The entrepreneur Richard Beard (1801-1885), whose employee was taking the pictures, was interested in everything he could make money from. That is why he had become fascinated by the new possibilities of photography. A few weeks after the new invention by he Frenchman Louis Daguerre (1787-1851) in 1839 he had acquired a license for his process for England and Wales. Knowing that Daguerre's process only produced a one-off image, Beard also took an interest in the calotype process invented by William Fox Talbot (1800-1877). Talbot’s pictures could be reproduced relatively easily, but Beard could not come to an agreement with the inventor.

|

| figure 1 |

The pictures were tiny, just 2 x 2.5 inches (5 x 6 cm), a format usually referred to as the “Ninth Plate”, because the plates originally produced for the photographs could be cut into nine pieces. But as many people were used to miniature paintings, which had been very en vogue before, this was not a problem, which left just one, problem to solve, and Beard again did what others didn't.

|

| Figure 2 |

The Frenchman Antoine Claudet (1797-1867), also held a license from Daguerre since 1839 and thanks to this was able to open his own studio in London in 1841, despite Beard’s license for the whole of England. Claudet used two cameras (figure 2). In this way he got two nearly identical pictures at once. Beard’s operator's used their relatively easy reloadable camera a to take two pictures in quick succession. As John Johnson also had invented a device for preparing and polishing the silver-coated copper photographic plates, there was no need to do this by hand anymore. Thus Beard’s operators were faster then Claudet's, as an astonished Journalist of The Spectator reported on 4 September 1841. This led to the erroneous surmise that Beard's camera allowed two photos to be taken at the same time by adjusting a mirror.

|

| Figure 3 |

Therefore, at the same time Beard also changed his camera. From then on, he used a camera that could take pictures in the "sixth plate" format, that is 2.75 x 3.25 inches (7 x 8 cm). Even the ever critical William Henry Fox Talbot called Johnson’s and Wolcott’s improved Daguerreotypes in March 1843 “the most perfect thing of the kind I have yet seen."

But unfortunately little is known about the new camera itself. The only thing certain is that it used the powerful lens newly invented by the Hungarian-German mathematician Joseph Petzval (1807-1891) and distributed throughout Europe by the Austrian optician Friedrich von Voigtländer (1812-1878).

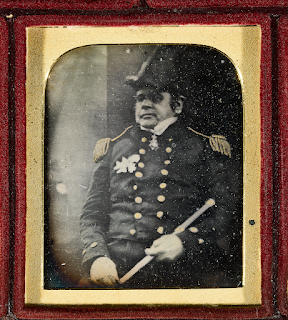

As the images were now taken with a lensed camera, it was usually assumed that they were now inverted. As the images of the Franklin expedition officers where taken with the same camera, it was (up to now) thought that the daguerreotypes of Sir John Franklin, Commander James Fitzjames, Lieutenant Henry Thomas Dundas Le Vesconte, the purser Charles H. Osmer and the surgeon Stephen S. Stanley from the collection of the Scott Polar Research Institute are originals, as well as the images of Captain Francis R. M. Crozier, James Fitzjames, the mate Charles Frederick Des Voeux, and the assistant surgeon Henry Goodsir, which have now surfaced, because these images are inverted, while the others would be copies. But as with everything related to the Franklin expedition, it is not that easy.

|

| Figure 4 |

|

| Figure 5 |

The problem with such a simple device was that it easily shifted, especially in windy conditions. Unfortunately, we neither know if it was used at all, if the camera was aimed at or past the sitter, nor what the wind conditions were like during that particular days. It may be that the camera operator sometimes used the correction mirror and sometimes not. It could very well be that all the newly discovered daguerreotypes are originals, whether or not they have been reversed. The two mirror-inverted shots of Fitzjames might indeed be originals, as they are not identical. The same may be true of the different shots of Des Voeux, although one is mirrored and the other is not. Perhaps the original also went to the family and one of the surviving daguerreotypes is a copy.

However, most of the surviving images of the officers of the Erebus, of which there are two identical photographs, are not reversed. If they are not both copies, then Beard's employees must even have made copies of copies, which may well be the case, given the high demand. James Fitzjames alone wanted three or four pictures, as he wrote in a letter. (see Potter et. al. May We Be Spared p. 117).

Looking at the Illustrated London News of 13 September 1851 (p. 329) does not help either. Although the images, or rather engravings after the daguerreotypes, finally appeared in the press the comment published with them tells us nothing about how they where taken. On the contrary: It even contains at least one major error: While it's true that Richard Beard had supplied the Franklin expedition with a complete Daguerreotype apparatus, as the author of the comment to the images explained, this was probably not the same camera with which the pictures were taken. As the polishing apparatus invented by Johnson in 1841 has been discovered in the wrack of HMS Erebus recently, we know, that the camera on board the ship must be Wolcott's original mirror camera, as the polishing device was made for ninth-plate images, as Peter Carney has noted. It's a forgivable mistake more than half a decade after the pictures were taken, especially as the author was not a specialist in daguerreotypes but rather in maritime matters, as it is none other than William Richard O’Byrne, (1823–1896) the author of the “Naval Biographical Dictionary” published two years earlier in 1849.

So what remains but confusion?

If photos were indeed only taken on one day, and the camera operator only came back on the second day to present the pictures, or if the studio was still in the same place on the second day as it was on the first, it may even be possible to tell from a close examination of the images whether and when a corrective mirror was used. For Daguerreotypes are so clear that one can sometimes sense the reflection of the camera and the camera operator behind it in the pupils of the sitter. Or since there is at least one shot (that of Le Vesconte) where you can see where he was sitting, you might even be able to tell from the reflections on the caps where the camera was pointed.

But this is a matter for others, for whom the question of whether it is an original or not is more important than for me and who, above all, have more patience than I .

The author would like to thank Gina Koellner, Mary Williamson, Peter Carney, Michael Robinson, Bill Schulz and last but not least Russell Potter for their inspiration and helpful comments.

Friday, August 25, 2023

The newfound Franklin Daguerreotypes

|

| Courtesy of Sotheby's |

"It's an extraordinarily different Crozier, despite being the exact same photograph. His face has quite literally been "fleshed out" now, with details added back in that we didn't know we were missing. His eyes and chin have much more definition, and somehow even his lips and nose look fuller in the new image. He simply looks like a different man. The worried, almost indecisive look from the old photograph melts away -- he looks like a Captain now, someone who gave orders."

|

| Image Courtesy Sotheby's |