Guest post by Frank Michael Schuster

The month of May 1845, when Sir John Franklin's expedition set sail started out as a cold and unfriendly one throughout Europe. An outbreak of the flu was raging in London, which had also caught the expedition's leader. But by mid-May the weather improved and the 15th and 16th of May were sunny and noticeably warmer than the days before and after. Perhaps that was why a camera operator, or as they called it in those days, a Daguerreotypist from one of Richard Beard's studios, was just then coming on board HMS Erebus. He had been commissioned by Lady Jane Franklin to take photographs of Sir John and the other officers of the flagship, as well as Franklin's second-in-command Francis Crozier. With the help of a heavy curtain and a simple wooden chair, a makeshift studio was created on deck, where the men, supervised by the officers, still stowed provisions and other supplies. This might be why the officers in the pictures are wearing only their "undress uniform" instead of one of the more formal ones usually more appropriate to the occasion. Some, like Lieutenant James Walter Fairholme, are not even wearing their coats given the surprisingly mild weather. For, when it was his turn to be photographed, he simply borrowed “Fitzjames' coat [...], to save myself the trouble of getting my own,” as he later wrote to his father (Potter et. al., May We Be Spared 146). Unfortunately, we know nothing about the wind on those days, but the camera operator obviously wanted to take advantage of the sunny day.

The entrepreneur Richard Beard (1801-1885), whose employee was taking the pictures, was interested in everything he could make money from. That is why he had become fascinated by the new possibilities of photography. A few weeks after the new invention by he Frenchman Louis Daguerre (1787-1851) in 1839 he had acquired a license for his process for England and Wales. Knowing that Daguerre's process only produced a one-off image, Beard also took an interest in the calotype process invented by William Fox Talbot (1800-1877). Talbot’s pictures could be reproduced relatively easily, but Beard could not come to an agreement with the inventor.

|

| figure 1 |

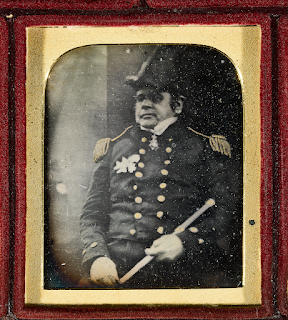

So Beard set out to solve the three major problems his customers had with the daguerreotype as quickly as possible: The exposure time was too long for portraits, the images were slightly distorted and mirror-inverted, and they could not be duplicated. By hiring the chemist John Frederick Goddard (1795-1866) and by using an American camera patented in March 1840 in England he was able to reduce the exposure time considerably to under a minute. As the inventors Alexander S. Wolcott (1804 -1844) & John Johnson (1813-1871) did not use a lens, but a concave mirror instead, the images were not reversed, and thus the second problem was solved. (figure 1) That the images were slightly distorted, just like today, hardly bothered anyone, apart from the Duke of Wellington, who complained that his nose was too big in the image.

The pictures were tiny, just 2 x 2.5 inches (5 x 6 cm), a format usually referred to as the “Ninth Plate”, because the plates originally produced for the photographs could be cut into nine pieces. But as many people were used to miniature paintings, which had been very en vogue before, this was not a problem, which left just one, problem to solve, and Beard again did what others didn't.

|

| Figure 2 |

The Frenchman Antoine Claudet (1797-1867), also held a license from Daguerre since 1839 and thanks to this was able to open his own studio in London in 1841, despite Beard’s license for the whole of England. Claudet used two cameras (figure 2). In this way he got two nearly identical pictures at once. Beard’s operator's used their relatively easy reloadable camera a to take two pictures in quick succession. As John Johnson also had invented a device for preparing and

polishing the silver-coated copper photographic plates, there was no need to do this by hand anymore. Thus Beard’s operators were faster then Claudet's, as an astonished Journalist of

The Spectator reported on 4 September 1841. This led to the erroneous surmise that Beard's camera allowed two photos to be

taken at the same time by adjusting a mirror.

|

| Figure 3 |

In early 1843 the problem of how to duplicate a daguerreotype was finally solved, when Wolcott and Johnson invented a copying apparatus. It was basically a daguerreotype camera to photograph daguerreotypes, which additionally was suitable for enlarging and could be used as a projector (figure 3). Using mirrors, the copy was reverted to the original. This meant, in order to obtain an identical image of the original, it was necessary to make a copy of the copy. The inventors themselves came to London to set it up in Beard's studios. After all, the customers had become more demanding and expected larger pictures.

Therefore, at the same time Beard also changed his camera. From then on, he used a camera that could take pictures in the "sixth plate" format, that is 2.75 x 3.25 inches (7 x 8 cm). Even the ever critical William Henry Fox Talbot called Johnson’s and Wolcott’s improved Daguerreotypes in March 1843 “the most perfect thing of the kind I have yet seen."

But unfortunately little is known about the new camera itself. The only thing certain is that it used the powerful lens newly invented by the Hungarian-German mathematician Joseph Petzval (1807-1891) and distributed throughout Europe by the Austrian optician Friedrich von Voigtländer (1812-1878).

As the images were now taken with a lensed camera, it was usually assumed that they were now inverted. As the images of the Franklin expedition officers where taken with the same camera, it was (up to now) thought that the daguerreotypes of Sir John Franklin, Commander James Fitzjames, Lieutenant Henry Thomas Dundas Le Vesconte, the purser Charles H. Osmer and the surgeon Stephen S. Stanley from the collection of the Scott Polar Research Institute are originals, as well as the images of Captain Francis R. M. Crozier, James Fitzjames, the mate Charles Frederick Des Voeux, and the assistant surgeon Henry Goodsir, which have now surfaced, because these images are inverted, while the others would be copies. But as with everything related to the Franklin expedition, it is not that easy.

|

| Figure 4 |

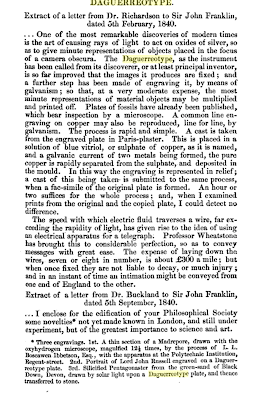

And yet, a year after the expedition had left England, Beard’s competitor Claudet proudly declared in an advertisement in

The Times on 20 May 1846 that all his portraits were now taken with “the right and left side in their natural position,” whereupon the angry Beard responded in the same paper on 9 June by pointing out that his pictures had always been non-reversed, "first by means of his patent concave reflector, and also (for more than three years past) by the use of a reflector in combination with a lens." (

The Times, 9 June 1846; figure 4).

|

| Figure 5 |

What this reflector looked like, we don’t know for sure, as we don’t know much about the camera improved by Johnson and Wolcott. The easiest solution to get a non-reversed image was to put an adjustable mirror in front of the lens at a 45° angle, as for example a lens marketed from the French photographer Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg (1810-1875) shows. (figure 5)

The problem with such a simple device was that it easily shifted, especially in windy conditions. Unfortunately, we neither know if it was used at all, if the camera was aimed at or past the sitter, nor what the wind conditions were like during that particular days. It may be that the camera operator sometimes used the correction mirror and sometimes not. It could very well be that all the newly discovered daguerreotypes are originals, whether or not they have been reversed. The two mirror-inverted shots of Fitzjames might indeed be originals, as they are not identical. The same may be true of the different shots of Des Voeux, although one is mirrored and the other is not. Perhaps the original also went to the family and one of the surviving daguerreotypes is a copy.

However, most of the surviving images of the officers of the Erebus, of which there are two identical photographs, are not reversed. If they are not both copies, then Beard's employees must even have made copies of copies, which may well be the case, given the high demand. James Fitzjames alone wanted three or four pictures, as he wrote in a letter. (see Potter et. al. May We Be Spared p. 117).

Looking at the Illustrated London News of 13 September 1851 (p. 329) does not help either. Although the images, or rather engravings after the daguerreotypes, finally appeared in the press the comment published with them tells us nothing about how they where taken. On the contrary: It even contains at least one major error: While it's true that Richard Beard had supplied the Franklin expedition with a complete Daguerreotype apparatus, as the author of the comment to the images explained, this was probably not the same camera with which the pictures were taken. As the polishing apparatus invented by Johnson in 1841 has been discovered in the wrack of HMS Erebus recently, we know, that the camera on board the ship must be Wolcott's original mirror camera, as the polishing device was made for ninth-plate images, as Peter Carney has noted. It's a forgivable mistake more than half a decade after the pictures were taken, especially as the author was not a specialist in daguerreotypes but rather in maritime matters, as it is none other than William Richard O’Byrne, (1823–1896) the author of the “Naval Biographical Dictionary” published two years earlier in 1849.

So what remains but confusion?

If photos were indeed only taken on one day, and the camera operator only came back on the second day to present the pictures, or if the studio was still in the same place on the second day as it was on the first, it may even be possible to tell from a close examination of the images whether and when a corrective mirror was used. For Daguerreotypes are so clear that one can sometimes sense the reflection of the camera and the camera operator behind it in the pupils of the sitter. Or since there is at least one shot (that of Le Vesconte) where you can see where he was sitting, you might even be able to tell from the reflections on the caps where the camera was pointed.

But this is a matter for others, for whom the question of whether it is an original or not is more important than for me and who, above all, have more patience than I .

The author would like to thank Gina Koellner, Mary Williamson, Peter Carney, Michael Robinson, Bill Schulz and last but not least Russell Potter for their inspiration and helpful comments.

.jpg)