Roddy had a privileged childhood, being sent to Eton which he always claimed to have hated, but the contacts he made there & later at Oxford would prove invaluable to him on his travels all over the world. It would be wrong, however to imply that money was plentiful. Roddy’s father George Fenwick-Owen had inherited sufficient money to lead a comfortable life, but lost everything in the financial crash of 1929, and to make matters worse, he then ran off with the governess, leaving Roddy & his two sisters to be brought up solely by their mother Bettina. She famously claimed that she had to make do on what was previously her “dress allowance”.

But travel could be managed on a shoestring, particularly when there were contacts who could secure a passage on a ship to far flung destinations. Through a friend of a friend, Roddy ended up as Assistant Purser on Clan Urquhart, a cargo ship travelling from Liverpool to Sydney, from where another friend used his influence to get him onto a cargo boat for Fiji. Roddy then spent a year beachcombing in the South Seas, during which he was seduced by, and married, a Polynesian princess called Turia. He left her and moved on, publishing his experiences when he returned to England in his first travel book Where the Poor are Happy (Collins, 1954) along with two more novels set in the South Seas, Green Heart of Heaven and Worse than Wanton.

Roddy’s particular interest in John Franklin began in the early 1970’s. His Aunt Susan, widow of Uncle John Rawnsley, who lived at Well Vale, Lincolnshire, expressed a wish to give “her” collection of books on John Franklin to Lincoln County Library. Roddy pointed out that they weren’t hers to give. They had been inherited by his grandfather Walter Rawnsley, then passed to his wife Maud & from her to Roddy’s mother Bettina, but without having been removed from Well Vale. The deed had already been done, but Roddy turned on the charm and managed to extract them from the County Librarian, and on reading through was well & truly hooked.

“Day and night, the North-West passage haunted me” he wrote in his memoirs. His recent biography on the life of Mavis De Vere Cole, Beautiful and Beloved (Hutchinson, 1974) had been well received, which left him in a good position to ask his agent Ann McDermid, her immediate reply being:

“John Franklin? – You mean Benjamin Franklin, don’t you?”

“No, John. Sir John of the Frozen North!”

“Oh, that one … we know a lot about him in Canada, of course. Well I can always put it up to Hutchinson’s”

And Hutchinson’s reply “Well, I think that’s absolutely splendid Roddy …” made it all plain sailing!

“I ought to visit the Arctic, if I’m going to write about it properly” were Roddy’s thoughts in 1976. He mentioned his predicament to his brother-in-law by marriage, a former Ambassador to the Holy See, who remarked “Why not get someone to send you there? It shouldn’t be beyond your ingenuity!” As it happened, August 1976 was the 150th anniversary of Franklin’s arrival at Prudhoe Bay, on the second land expedition. Roddy contacted BP, who were already interested in celebrating this event and were delighted to involve a descendant of Sir John Franklin. They wanted a monument in Anchorage, Alaska.

Roddy suggested using just the head of the Franklin figure standing on a plinth in Spilsby Town Square. Nobody had ever seen his head at eye level before. (Russell, Gina, Steve & I located Franklin’s head in Anchorage in 2019 & Steve took this photo) A further plaque would be placed at Deadhorse Airport, for which Roddy agreed to compose the words, make a short speech & unveil it.

Roddy managed to visit various key places, the first being Franklin’s furthest point west at Return Reef. It seemed likely that the reef had been washed away, so the helicopter landed on Stump Island nearby. Next on the agenda was Winter Lake by seaplane, to locate the site of Fort Enterprise. Roddy remarked in his memoir “The whole settlement had disappeared, almost without trace …. Even when sitting on the site of Fort Enterprise I found it impossible to reconstruct the Franklin party’s experiences realistically. Nothing fitted my preconceptions. Things as I’d thought they would be, had to be replaced by things as they were. I felt a distinct sense of loss.”

|

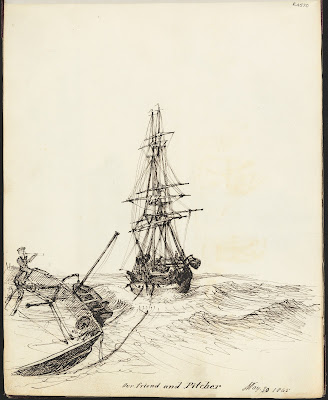

| Owen with the mast of the Mary |

Roddy was taken to Beechey Island with a fishing party of Americans who were going on to Cresswell Bay. He & his Inuit guide Andrew were left on Beechey at 7:30am & remained there until picked up by the twin otter at 4pm. They had plenty of time to explore – Roddy noted “the spar of John Ross’ ship “Mary” sticking up at an angle.” They attempted to climb to the top of the hill to see the cairn, but it was too much for Roddy & he had to signal to Andrew “who must have thought me a proper softy”

I remember Roddy being particularly pleased to get the contract for The Fate of Franklin, because, as he explained to us at the time, “I can now write the book that I want to write” Roddy always acknowledged the help he received from the mystical “Unseen”. He used to tell us that when faced with a huge pile of papers, an unseen presence would guide him to the right folder. He believed this to be the spirit of his great-uncle Willingham Franklin Rawnsley (1845-1927), great nephew and Godson of Sir John, who wrote The Life, Diaries and Correspondence of Jane Lady Franklin (1923).

In spite of Willingham’s ghostly presence, Roddy’s methods of research were somewhat haphazard. His desire “not to pepper the text with little stars” led to the main criticism of his book, which was his total lack of sources, either as footnotes or a separate list. As for filing and maintaining research material afterwards, this was also hit & miss, as he explained in his memoirs:

“It had always been my habit to jettison the huge quantity of facts involved in writing any biography as quickly as possible; otherwise I might have gone mad”

Exactly how much was jettisoned is impossible to know.

After Roddy’s death I found letters from researchers amongst his papers enquiring about sources post publication, along with copies of Roddy’s replies, most of which supplied absolutely no information, albeit very politely! In spite of this, Roddy was always very accommodating towards Franklin researchers. A young Dave Woodman was given lunch & shown Roddy’s precious Staffordshire figures of Sir John & Jane Franklin, as well as being taken to the Royal Geographical Society Library.

I think Roddy was disappointed that there was no separate American edition of his book.

In a letter to author Sten Nadolny (The Discovery of Slowness, Viking Penguin 1987) in 1981, he wrote:

“The Fate of Franklin … did well but not very well. I wasn’t nearly as successful as Jane Franklin in enlisting American support”

Although he often claimed to have forgotten everything, Roddy’s interest in Franklin remained and he was pleased to be asked to give an address at the Naval Chapel, Greenwich, in 1986 to mark the bicentenary of Sir John Franklin’s birth.

.jpeg) |

| Gilston Lodge |

One of Roddy’s greatest inherited treasures was the last known letter written by John Franklin to his wife from the Whale Fish Islands, and one of the letters in

May we be Spared … We failed to locate the letter before Roddy died, he couldn’t remember anything about it, so there was a great hunt for it afterwards. Eventually and very appropriately, it was discovered tucked into the back of Willingham Rawnsley’s draft copy of “The Life, Diaries and Correspondence of Jane Lady Franklin”. We found it in the small attic room above the Tower Room at the top of Gilston Lodge. Accessible by ladder only, the room was boiling hot in summer, freezing cold in winter and home to numerous ladybirds who seemed to have chomped through a good deal of photocopied material but left Willingham’s draft undisturbed.

Visiting Roddy at his house in London (Gilston Lodge) was always an experience. Meals were eaten in the kitchen, at a small table with huge winged chairs, all taken from a Victorian railway carriage, complete with brass lamps & polished brass luggage rack above. There was always a dog, the most recent one being a shih tzu called “Lovey” who had been notoriously difficult to house train but was adored nonetheless.

There was a very particular morning routine. After breakfast, Roddy would help the dog into the back of the car (never the boot!) and we would drive to Chiswick Park for a walk, the route being entirely decided by the dog. Whichever path he chose to go down, we would duly follow.

In the 1990’s Roddy started writing his autobiography, which ended up as three large volumes. His desire for truth, warts and all, laid bare his pursuit of love for both sexes. It was a life of joyous promiscuity until he met the love of his life in 1967, an Italian man named Gian Carlo Pasqualetto. Roddy preferred London to the countryside, though he did risk the occasional visit to my parents farm. It always amused us that someone who had been stranded in far flung places & coped with all manner of tricky situations was unwilling to subject his smart London car to a ½ mile driveway of potholes, brambles & cowpats. But that was all part of Uncle Roddy’s charm!

Gilston was always full of people. There was a lodger on the top floor for many years, a couple in the basement, and of course Gian Carlo. No-one in the family ever commented on their relationship and we were left to work it out for ourselves. When his three autobiographical volumes were printed privately, Roddy was most disappointed that we weren’t more shocked by his many revelations!

Roddy appointed two Literary Executors to administer his literary estate, with the express wish that his autobiography be published after his death. “I would be most unhappy to think that any parts of this long memoir should be cut on grounds of “decency”, for those bits are essential”

The length of the combined volumes meant that inevitably, some bits were cut, but two paperback volumes Travels of Delight and Tours of Delight edited by Nigel Hart were published by Langney Press in 2016. A more recent version which included more of the “essential” bits was edited by Emily Barrett of Little, Brown Book Group & published by Sphere in 2021 under the title Oh, What a Lovely Century.

When our own book,

May we be Spared to Meet on Earth: Letters of the Lost Franklin Arctic Expedition required funding, I approached the nearest Literary Executor, my brother Charles. Both he and his co-executor agreed that Roddy would have been delighted to help out, so a cheque was duly handed over to me, with a bust of Sir John Franklin in the background looking on approvingly!

.jpeg)